Hijacking GitHub Repositories by Deleting and Restoring Them

Recently, we encountered an obscure security measure while researching GitHub repositories: the popular repository namespace retirement. This security measure was implemented by GitHub to protect (popular) repositories against repo jacking (i.e. hijacking attacks).

During this research, we discovered a way to bypass the popular repository namespace retirement. We reported this to GitHub, and they fixed the problem. In this post, we will discuss what the popular repository namespace retirement is, what attacks it is trying to protect against and how we (and others) were able to bypass it.

Repo Jacking

GitHub repository names are not unique. They fall under the namespace of their owner. For example, the repository of this blog is uniquely identified as joren485/blog, even though are many other repositories that are called blog. This means that when a GitHub user renames their account, the namespace of all their repositories change too. For example, if a user boring-github-user with a repository boring-github-user/repo changes their name to fancy-new-github-user, the repository is now identified as fancy-new-github-user/repo.

But what happens to the old repository name (i.e. boring-github-user/repo) after a username change? To help downstream processes that depend on the repository (e.g. packages, build processes, CI pipelines, etc.) find the correct repository, GitHub sets up a redirect from the old repository name to the new repository (e.g. anyone cloning boring-github-user/repo would actually clone fancy-new-github-user/repo instead).

GitHub frees up the old username after a name change and allows other users to claim it. When another account uses the username, they can break the redirect by creating a repository with the same name as the redirected repository.

This creates the possibility for an attacker to hijack repositories owned by renamed users: repo jacking.

Let’s look at how such attacks work with an example:

- A victim user has a GitHub account

victimand a repositoryvictim/python-package. - The victim decides to change their GitHub username to

fancy-victim. The name of the repository now also changes tofancy-victim/python-package. - To help downstream packages find

victim/python-packageafter the name change, GitHub sets up a redirect fromvictim/python-packagetofancy-victim/python-package. - An attacker notices the name change of

victimand deliberately registers a new account with the namevictim. - The attacker creates a repository

victim/python-package. This removes the redirect that GitHub set up in step 3. - Now all downstream packages that reference

victim/python-packagewill reference code that the attacker controls and not the original, legitimate repository.

If you want to learn more about repo jacking attacks, I suggest reading Repo Jacking: Exploiting the Dependency Supply Chain.

Popular Repository Namespace Retirement

To protect users against repo jacking attacks, GitHub implemented a security mechanism called the “popular repository namespace retirement”. This feature blocks users from creating a repository, if the repository existed previously and got 100 clones in the week before the name change.

Using our above example, if victim/python-package got 100 clones in the week that victim changed their username, the attacker would still be able to register a new account with the username victim, but would not be able to create a new repository victim/python-package.

Previously Found Bypasses

Earlier this year, Checkmarx published two ways to bypass the popular repository namespace retirement. Both of these bypasses allow attackers to get full control over a repository that should be retired.

-

GitHub RepoJacking Weakness Exploited in the Wild by Attackers (2022-05-27)

The first bypass they found involved renaming an account:

- Let’s say we want to create a repository

victim/repothat is protected by namespace retirement. - Create a new GitHub account

victim2. - Create a repository

victim2/repo. - Rename

victim2tovictim. - We are now the owner of

victim/repo.

- Let’s say we want to create a repository

-

Attacking the Software Supply Chain with a Simple Rename (2022-10-26)

The second bypass they found involved transferring a repository:

- Create the target GitHub account

victim. - Create another GitHub account

victim-helper. - Create a repository

victim-helper/repo. - Transfer

victim-helper/repotovictim. - We are now the owner of

victim/repo.

- Create the target GitHub account

GitHub fixed both bypasses after Checkmarx reported them.

Deleted Repositories

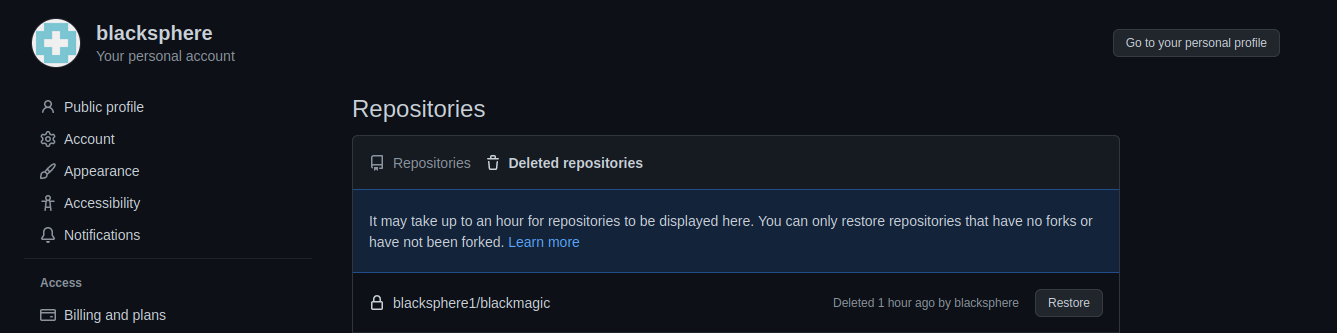

In 2019, GitHub added a feature that allows GitHub users to restore deleted repositories, for 90 days after deletion.

When a user deletes a repository, they are able to restore it by going to the “deleted repositories” tab on the “Repositories” page in their settings, as long as the repository was not forked and was deleted between 1 hour and 90 days ago.

Restoring Retired Repositories

What happens if we try to restore a repository that is protected by namespace retirement? Let’s find out!

To test this, we need a repository that is retired. We will use blacksphere/blackmagic for this. The blacksphere account was renamed to blackmagic-debug, so blacksphere/blackmagic now redirects to blackmagic-debug/blackmagic.`

Disclaimer: I am in no way affiliated with the previous owners of the blacksphere GitHub account and choice blacksphere/blackmagic because it was the first repository protected by the popular repository namespace retirement that I found.

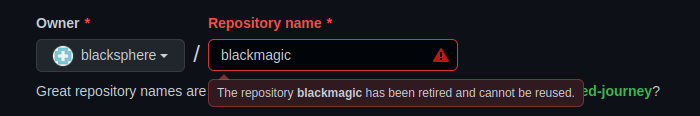

Because the account was renamed, blacksphere is now an available username. We registered a new blacksphere account. When we try to create a repository called blackmagic, we get an error that tells us that the repository is retired:

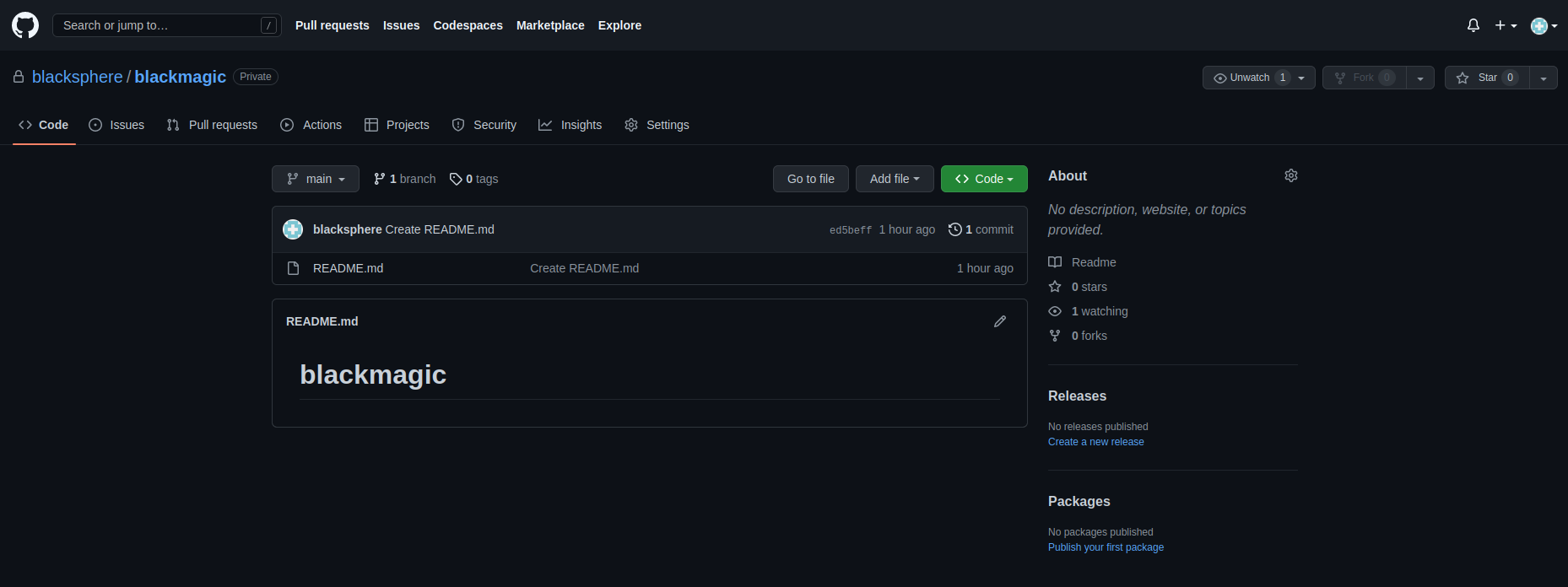

We can, of course, create a repository blackmagic if we rename our account (e.g. to blacksphere1), because blacksphere1/blackmagic is not retired. As with any standard repository, we are also able to delete blacksphere1/blackmagic and restore it.

It turns out, we are still able to restore blacksphere1/blackmagic if we rename our account back to blacksphere:

This is interesting! What happens if we restore this repository? Our account is not named blacksphere1 anymore, so the repository cannot be restored as blacksphere1/blackmagic anymore. Well, it turns out the repository is restored using our current username (i.e. blacksphere/blackmagic):

We have created a repository that is retired, fully bypassing the protected by popular repository namespace retirement.

Because we have created blacksphere/blackmagic it no longer redirects to blackmagic-debug/blackmagic. Luckily, the redirect is restored when we delete blacksphere/blackmagic.

The Attack in Steps

Let’s look at how an attacker would use this bypass to hijack GitHub repositories.

- The attacker finds a repository that falls under the popular repository namespace retirement. For example,

victim/python-package. - They register a new GitHub account (with another name than the target). For example,

victim1. - They create the target repo as the new GitHub account. In our example,

victim1/python-package. - They delete the

victim1/python-packagerepository. - They Rename

victim1tovictim- This is possible, because

python-packageis no longer a repo ofvictim1.

- This is possible, because

- Wait for 1 hour.

- Repositories are only restorable after one hour after their deletion.

- Restore

victim1/python-package.- As the account is not named

victim1anymore, butvictim, the deleted repository gets restored asvictim/python-package.

- As the account is not named

- They now have full control over

victim/python-package.

Discussion

This is the third bypass of popular repository namespace retirement. All three bypasses rely on non-standard ways to create repositories. This indicates that there is no central check to verify a repository isn’t retired when it is created. If this assumption is correct, there may well be other bypasses still out there.

While popular repository namespace retirement is an obscure security mechanism, it is important, because tens of thousands of GitHub repositories are vulnerable to repo jacking. It is already a relatively weak security mechanism, because the vast majority of repositories do not fall within its requirements. For example, I would venture to say that 90+% of GitHub repositories get less than 100 clones a week. Being able to bypass it means that popular repositories also become vulnerable to repo jacking. These types of bypasses are being actively used by malicious actors to deploy malicious content.

When an attacker is able to successfully perform a repo jacking attack, all packages that use the repository will now use malicious code. As with all supply chain vulnerabilities, this does not only apply to packages that use the hijacked repository directly, but also for all packages that use the hijacked repository indirectly. This allows an attacker to impact many downstream packages by only hijacking one vulnerable repository.

What makes repo jacking even more potent, are the redirects that GitHub sets up when users change their name. Because of these redirects, name changes happen transparently to any downstream packages.

The best way to protect yourself against repo jacking attacks is to always reference GitHub repositories directly and not rely on GitHub redirects. Unfortunately, users are not warned when they follow a redirect.

Disclosure Timeline

All times are in CEST.

- 2022-11-11 23:52: I Notified GitHub (through their HackerOne program).

- 2022-11-14 20:06: First response from GitHub.

- 2022-11-17 00:42: GitHub confirmed the bug.

- 2022-12-01 21:18: GitHub notified me that they resolved the issue and rewarded me $4000.

I would like to again thank the GitHub team for the pleasant bug bounty experience.